Offshore wind power has been rapidly expanding worldwide, with costs steadily declining and the technology becoming established as a major source of electricity. In contrast, Japan’s offshore wind market is still often described as “high-cost” or “economically challenging,” and concerns over project viability continue to surface.

However, the challenges facing offshore wind in Japan are not simply a matter of expensive technology or equipment. Rather, Japan’s cost structure is shaped by a combination of port and construction constraints, grid limitations, institutional design, and financial conditions, all of which interact in ways that differ fundamentally from more mature overseas markets.

In particular, relying solely on LCOE (Levelized Cost of Energy) to assess project viability in Japan can be misleading. While LCOE remains an important benchmark, it does not fully capture the realities of offshore wind development in Japan, where CAPEX, OPEX, auction design, Promotion Zone conditions, and withdrawal risk have a direct and often decisive impact on actual project returns.

This article provides a structural overview of offshore wind cost economics, starting from the basic cost components and moving toward the specific characteristics of the Japanese market. We examine the differences between bottom-fixed and floating offshore wind, compare Japan with European markets, discuss the strengths and limitations of LCOE as an evaluation metric, and analyze cost and profitability trends across Japan’s offshore wind Promotion Zones.

The objective of this Pillar article is not to label offshore wind as “cheap” or “expensive.” Instead, it aims to clarify which factors act as bottlenecks, where project feasibility diverges, and under what conditions offshore wind can realistically become investable in Japan. By doing so, this article seeks to provide a shared analytical framework for investors, developers, and policymakers evaluating Japan’s offshore wind market from a long-term, execution-focused perspective.

Chapter 1: Offshore Wind Cost Structure (CAPEX / OPEX)

Understanding the economics of offshore wind begins with a clear view of its cost structure. In most markets, offshore wind costs are broadly divided into CAPEX (capital expenditure) and OPEX (operating expenditure). While this classification is universal, the balance and behavior of these costs in Japan differ markedly from those in more mature offshore wind markets.

A key characteristic of the Japanese market is that offshore wind is not necessarily expensive because of equipment prices alone. Rather, the conditions required to deploy that equipment are structurally demanding, and those demands translate directly into higher and more volatile costs.

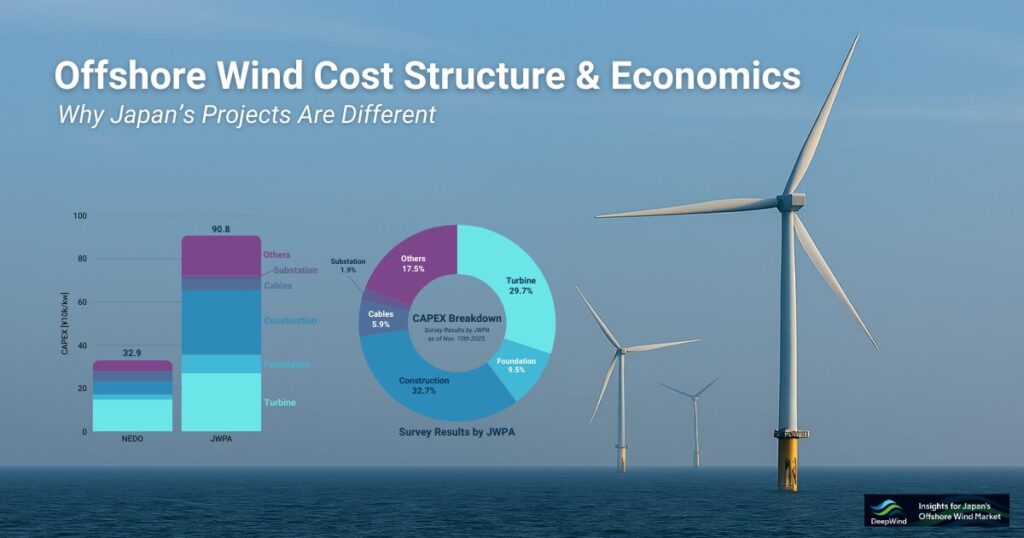

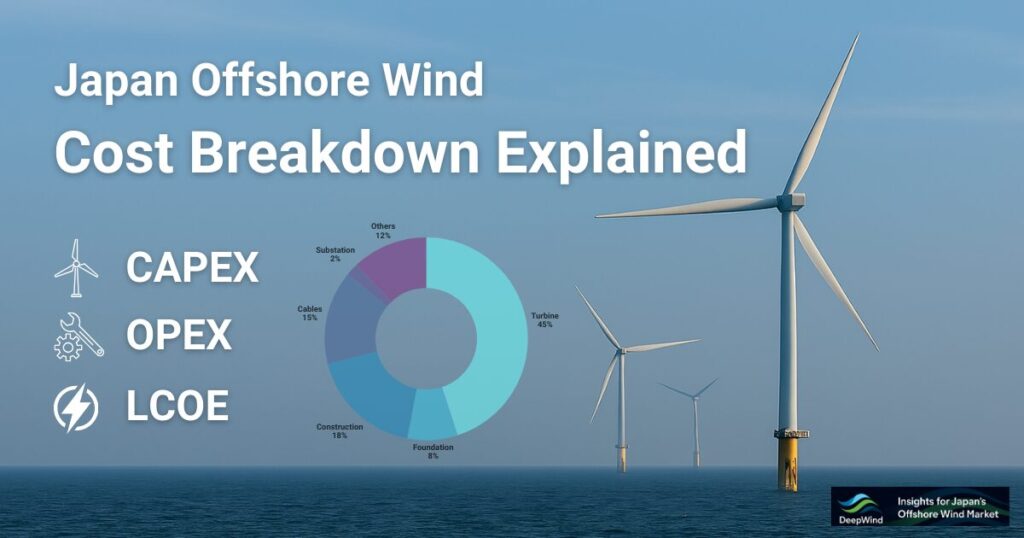

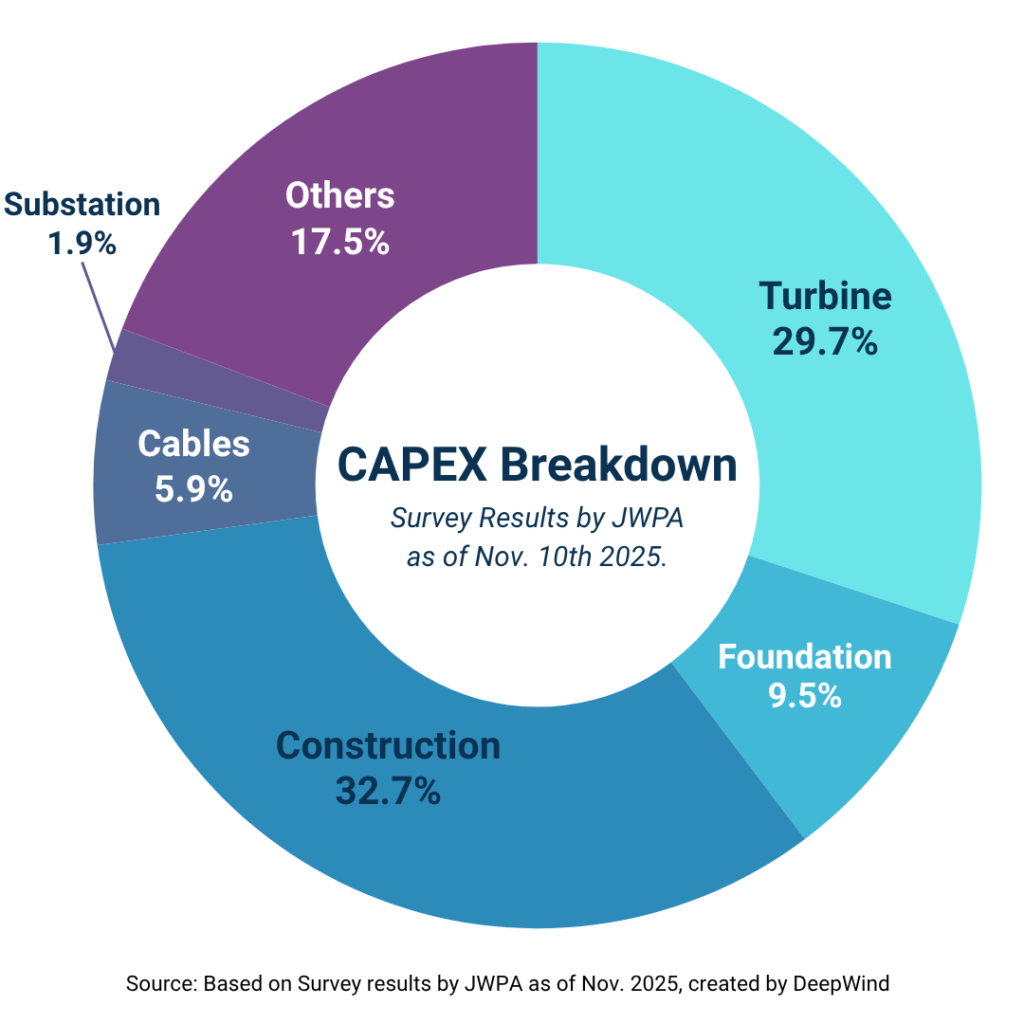

1.1 CAPEX: Capital Expenditure

CAPEX refers to the upfront investment required to construct an offshore wind farm. Regardless of whether a project is bottom-fixed or floating, CAPEX typically accounts for the majority of total lifecycle costs in offshore wind development.

Major CAPEX components include:

- Wind turbines: nacelles, blades, and towers

- Foundation structures

- Bottom-fixed: monopiles, jackets, etc.

- Floating: semi-submersible, spar-type platforms, and related structures

- Subsea cables and offshore substations

- Transportation and installation: construction vessels, port usage, towing, and offshore works

In Europe, many of these elements are already standardized. Ports are designed for offshore wind assembly, installation vessels are readily available, and supply chains operate at scale. As a result, CAPEX is relatively predictable and benefits from accumulated learning effects.

In Japan, by contrast, the underlying assumptions differ from project to project. Port availability, lifting capacity, storage areas, and installation logistics are often constrained. Even for bottom-fixed projects, limited port functionality can force longer transport distances, more complex installation sequences, or reliance on specialized vessels—each of which drives CAPEX upward.

Importantly, this cost inflation is not caused by turbine prices themselves, but by execution conditions. In many cases, the same turbine model may be used globally, yet total CAPEX diverges significantly due to local infrastructure and construction constraints.

For floating offshore wind, CAPEX volatility is even more pronounced. Platform fabrication, mooring systems, anchors, and dynamic cables introduce additional cost elements, while the lack of standardized designs amplifies uncertainty. As a result, floating projects tend to exhibit wider CAPEX dispersion than bottom-fixed projects at the current stage of market maturity.

In Japan, however, CAPEX volatility is driven less by turbine pricing and more by execution conditions such as port availability, installation logistics, and project-specific infrastructure constraints, as detailed in our Japan offshore wind cost analysis.

For floating projects, this effect is further amplified by non-standardized platform designs, mooring systems, and dynamic cables, which are discussed in depth in our analysis of floating offshore wind cost structures and LCOE.

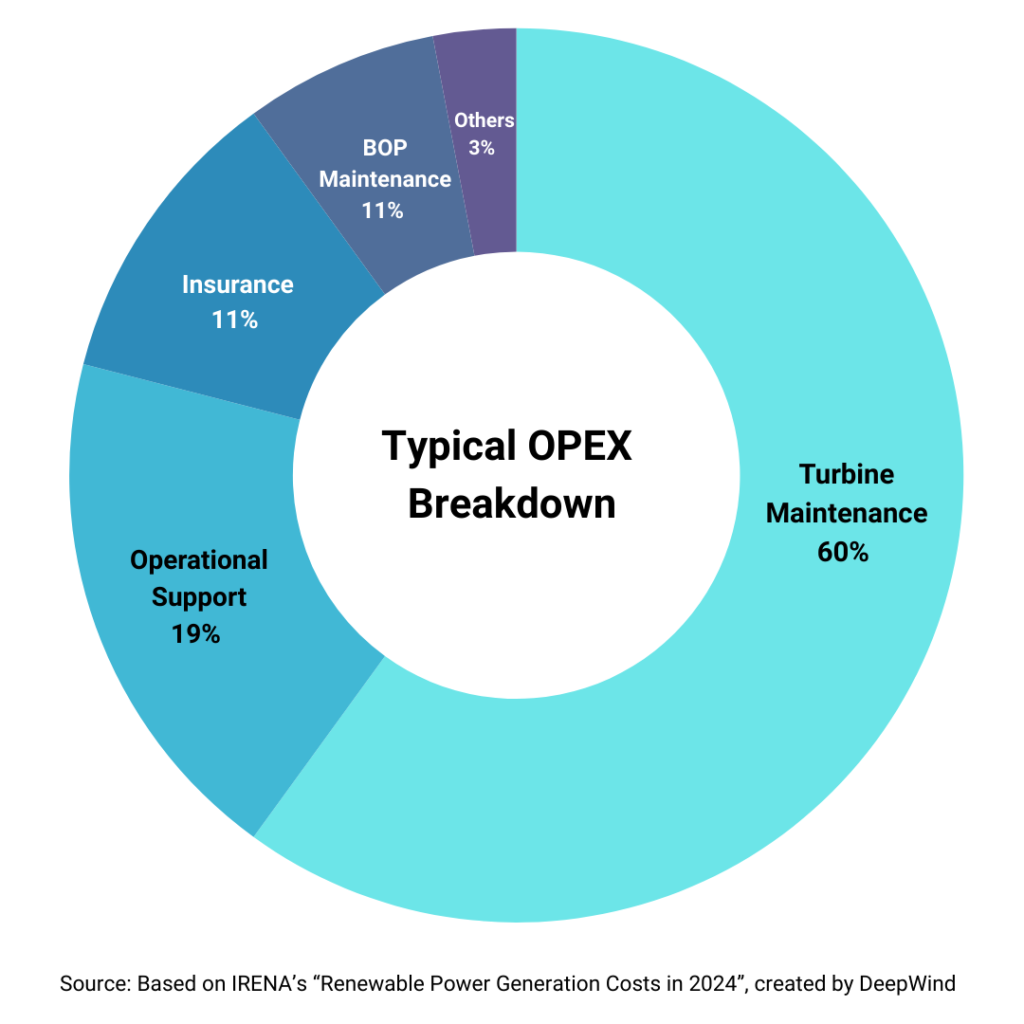

1.2 OPEX: Operating Expenditure

OPEX represents the recurring costs incurred after commissioning and throughout the operational lifetime of an offshore wind farm. Given project lifetimes of 20–30 years, OPEX plays a critical role in determining long-term profitability.

Typical OPEX components include:

- Routine inspections and scheduled maintenance

- Corrective repairs and component replacement

- Operations and asset management

- Insurance and port usage fees

- Chartering of service vessels

In Japan, OPEX is also structurally higher than in many European markets. The primary driver is environmental and operational uncertainty, rather than operational inefficiency.

Even for bottom-fixed projects, winter conditions in the Sea of Japan and long-period swells on the Pacific coast significantly restrict access windows for maintenance activities. These construction and maintenance windows—periods when offshore work can safely be conducted—are narrower and less predictable than in much of Northern Europe.

As a result, vessels often remain on standby for extended periods, increasing costs without contributing to productive work. Delayed maintenance can further elevate long-term risk and insurance premiums, compounding OPEX pressure.

For floating offshore wind, additional factors come into play. Mooring systems, dynamic cables, and floating platform behavior require specialized monitoring and inspection regimes. While future concepts envision towing floating units back to port for major maintenance, such approaches remain largely at the demonstration stage.

At present, floating offshore wind OPEX should be viewed as a cost category that has not yet fully benefited from learning effects. Technological innovation is advancing, but measurable cost reductions have not yet been consistently realized at scale.

In summary, Japan’s offshore wind OPEX is shaped less by labor productivity and more by natural conditions and infrastructure limitations. These constraints directly affect both cost levels and risk profiles over the project lifetime.

Chapter 2: LCOE — What It Explains, and What It Misses in the Japanese Market

Chapter 2: LCOE — What It Explains, and What It Misses in the Japanese Offshore Wind Market

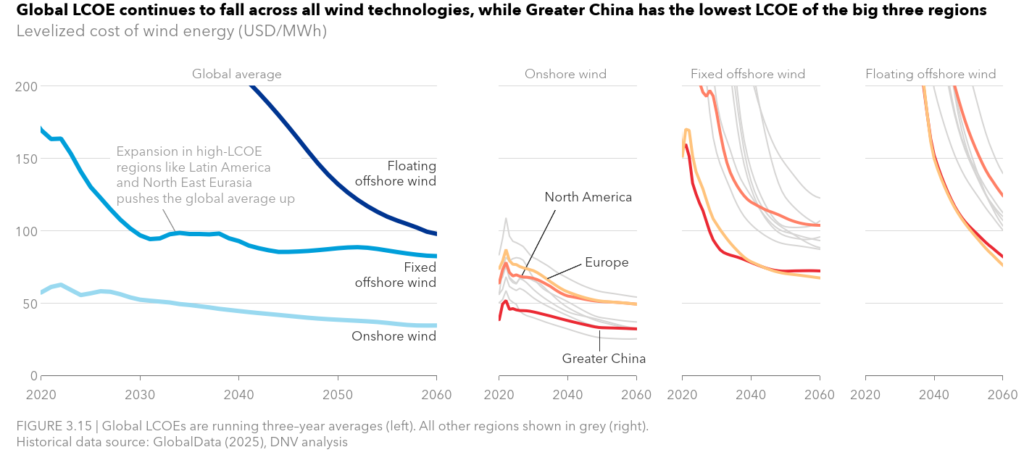

LCOE (Levelized Cost of Energy) is one of the most widely used indicators for assessing the cost competitiveness of power generation technologies. By averaging total lifecycle costs over total electricity generation, LCOE provides a simple, comparable metric across technologies and regions.

Globally, offshore wind has demonstrated a clear long-term LCOE reduction trend, driven by turbine upscaling, supply chain maturation, and accumulated project experience. However, in the Japanese offshore wind market, relying on LCOE alone can be misleading.

This is not because LCOE is a flawed metric, but because many of the risks that dominate project outcomes in Japan are only weakly reflected in LCOE calculations.

2.1 What LCOE Captures — and What It Does Not

LCOE is well suited for:

- Comparing different generation technologies

- Tracking long-term cost reduction trends

- Benchmarking regional or national markets

However, LCOE does not explicitly capture several factors that are critical in Japan:

- Construction schedule delays and cost overruns

- Port availability and installation logistics constraints

- Weather-driven downtime and narrow construction windows

- Financing conditions, risk premiums, and WACC sensitivity

As a result, projects with similar modeled LCOE values can exhibit materially different real-world cash flow outcomes.

This structural gap between modeled costs and realized economics is examined in detail in Japan Offshore Wind Cost Analysis , which shows how execution conditions, rather than equipment prices, often drive cost volatility in Japan.

2.2 Why LCOE Often Appears Overly Optimistic in Japan

In the Japanese offshore wind market, LCOE tends to look more favorable on paper than projects ultimately prove to be. This is largely due to how site-specific constraints interact with standardized cost models.

For example, limited construction windows caused by seasonal weather conditions can significantly increase installation vessel standby time and overall project duration. While these effects raise actual CAPEX and OPEX, they may only marginally affect modeled LCOE assumptions.

Similarly, port constraints and long mobilization distances can introduce cost escalation and scheduling risk that are difficult to fully internalize in early-stage LCOE modeling.

A comparative, zone-by-zone assessment of how these factors influence project economics can be found in Cost and IRR Analysis of Japan’s Offshore Wind Promotion Zones .

These discrepancies help explain why some projects that appeared competitive on an LCOE basis struggled to maintain financial viability once execution risks became clearer.

2.3 From LCOE to IRR: Why Investment Metrics Are Shifting

Because LCOE focuses on average generation cost, it does not directly answer the core investment question: does this project generate sufficient returns for the risk taken?

In contrast, IRR (Internal Rate of Return) incorporates not only CAPEX and OPEX, but also revenue assumptions, financing structures, and risk premiums. As a result, IRR is far more sensitive to the uncertainties that characterize the Japanese offshore wind market.

The limitations of LCOE-centered competition became evident in early project withdrawals, where projects with low bid prices failed to secure sustainable financing. This dynamic is analyzed in Japan Offshore Wind Round 1 Withdrawal: Policy Lessons .

In response, recent policy reforms have begun to shift emphasis away from pure price competition and toward execution feasibility and risk realism. An overview of these reforms is provided in Japan Offshore Wind Auction Reform (2025) .

In the Japanese context, LCOE should therefore be treated as a reference indicator, not a decision rule. Meaningful investment decisions require LCOE to be interpreted alongside IRR, risk allocation, and site-specific execution constraints.

With this in mind, the next chapter examines how these dynamics differ structurally between bottom-fixed and floating offshore wind, and why technology choice alone does not determine project economics in Japan.

Chapter 3: Bottom-Fixed vs Floating Offshore Wind — Where the Cost Gap Really Comes From

In discussions about offshore wind economics, the comparison between bottom-fixed and floating offshore wind is often simplified into a single conclusion: floating is more expensive.

While this is broadly true at present, such a conclusion obscures the more important question for the Japanese market: why the cost gap exists, and which parts of it are structural rather than temporary.

In Japan, the distinction between bottom-fixed and floating offshore wind is not merely a technological choice. It reflects differences in site conditions, construction logistics, risk allocation, and market maturity that directly shape project economics.

3.1 CAPEX Structures: Different Cost Drivers, Not Just Different Technologies

The largest and most visible cost difference between bottom-fixed and floating offshore wind appears in CAPEX. However, the sources of this difference are often misunderstood.

- Bottom-fixed offshore wind: foundations (monopile or jacket), seabed preparation, installation vessels, export cables

- Floating offshore wind: floating platforms, mooring systems, anchors, dynamic cables, towing and hook-up operations

In bottom-fixed projects, CAPEX is dominated by heavy offshore construction work. Costs scale with water depth, seabed conditions, and the availability of large installation vessels. Once suitable ports and vessels are secured, cost variability tends to narrow.

In floating projects, by contrast, the foundation itself becomes a complex engineered structure. Floating platforms resemble offshore vessels more than civil structures, with higher steel volumes, stricter fabrication tolerances, and greater quality control requirements.

While floating systems reduce the need for heavy offshore piling work, this advantage is offset by the added cost of mooring systems, anchors, and dynamic power cables. As a result, current floating CAPEX remains significantly higher than that of bottom-fixed projects.

A detailed breakdown of floating CAPEX and its implications for LCOE is provided in Cost Structure and LCOE of Floating Offshore Wind .

3.2 OPEX Implications: Where Long-Term Differences Emerge

Cost differences between bottom-fixed and floating offshore wind do not stop at construction. Over a 20–30 year project lifetime, OPEX plays an equally critical role.

- Bottom-fixed projects benefit from established access methods and standardized maintenance practices

- Floating projects require ongoing inspection of moorings, anchors, and dynamic cables

Floating systems introduce additional fatigue mechanisms and monitoring requirements that increase maintenance complexity. Mooring line wear, anchor integrity, and platform motion must be managed continuously.

At the same time, floating wind offers a potential long-term advantage: the possibility of towing turbines back to port for major maintenance. If realized at scale, this could reduce offshore working hours and safety risks.

However, in Japan, such operational concepts remain largely at the demonstration stage. As of today, floating OPEX should be viewed as structurally higher and more uncertain than that of bottom-fixed projects.

3.3 LCOE Differences Reflect Market Maturity, Not Technical Limits

Global benchmarks often show floating offshore wind LCOE at two to three times that of bottom-fixed offshore wind. This gap is frequently interpreted as evidence of inferior technology.

In reality, the gap primarily reflects differences in market maturity and deployment scale.

- Bottom-fixed offshore wind has accumulated decades of deployment and standardization

- Floating offshore wind remains in early commercial and large-scale demonstration phases

Standardized designs, repeatable construction processes, and mature supply chains have allowed bottom-fixed costs to converge. Floating offshore wind, by contrast, still exhibits wide design diversity, which limits learning effects and cost convergence.

Japan is actively attempting to address this issue through platform standardization and common design concepts. The technological rationale and limitations of this approach are discussed in Common Platform Development for Floating Offshore Wind .

Demonstration projects also play a critical role in validating assumptions about cost, constructability, and operations. Japan’s Phase 2 floating demonstration projects illustrate both the progress made and the challenges that remain: Floating Offshore Wind Demonstration Projects (Phase 2) .

3.4 The Japanese Reality: Choice Is Often Determined by Geography

In many global markets, developers can choose between bottom-fixed and floating solutions based on cost optimization. In Japan, this choice is frequently constrained by geography.

- Water depths up to roughly 50–60 meters: bottom-fixed solutions may be feasible

- Steeper seabed and deeper waters: floating solutions become unavoidable

This means that floating offshore wind in Japan is not a future option, but a present necessity for accessing large portions of the resource base. The relevant question is therefore not whether floating is more expensive, but how its costs can be managed and reduced under Japanese conditions.

This reality reinforces a key insight: technology choice alone does not determine project viability. Port infrastructure, installation logistics, financing conditions, and policy design are equally decisive.

The next chapter examines how Japan’s auction system and policy framework have interacted with these technological realities, and how institutional design has amplified—or mitigated—cost and risk.

Chapter 4: Policy and Auction Design — How Institutions Shape Offshore Wind Costs in Japan

Offshore wind project costs are often discussed in terms of technology and site conditions. However, in Japan, policy design and auction rules have played an equally decisive role in shaping cost structures and investment outcomes.

Rather than simply lowering costs, Japan’s institutional framework has, in some cases, reallocated risks in ways that amplified financial fragility. Understanding this interaction is essential to interpreting recent project withdrawals and ongoing policy reforms.

4.1 Price-Centric Auctions and Their Structural Side Effects

In its early rounds, Japan’s offshore wind auction system placed strong emphasis on offered FIT/FIP prices. This created an environment where competitive success depended primarily on how low developers could bid.

While this approach achieved headline price reductions, it also produced several structural side effects:

- Optimistic assumptions about future cost reductions

- Underestimation of supply chain and installation constraints

- Compressed IRR margins with limited buffer for cost escalation

In practice, this meant that projects could appear viable on paper while remaining highly sensitive to even modest changes in CAPEX, OPEX, or financing conditions.

This fragility was not immediately visible through LCOE comparisons, but became evident once projects moved closer to construction and financing milestones.

4.2 Round 1 Withdrawals: A Systemic Signal, Not an Isolated Failure

The withdrawal of several Round 1 offshore wind projects marked a turning point for Japan’s offshore wind policy debate. These decisions were often portrayed as company-specific or circumstantial, but such interpretations miss the broader picture.

The withdrawals reflected a convergence of structural pressures:

- Rising material and installation costs

- More conservative lending conditions

- Reassessment of construction schedules and offshore risks

Crucially, these pressures exposed the limits of auction designs that prioritized price signals over execution resilience.

A detailed institutional analysis of the Round 1 withdrawals, including the policy implications identified by METI, is provided in Japan Offshore Wind Round 1 Withdrawals: METI’s Analysis .

4.3 Auction Reform: From Price Competition to Project Viability

In response to these outcomes, Japan has begun to recalibrate its offshore wind auction framework. Recent reforms reflect a shift away from pure price competition toward greater emphasis on feasibility, risk allocation, and long-term stability.

Key directions of reform include:

- Greater scrutiny of execution capability and project realism

- Improved alignment between bid assumptions and financing conditions

- Explicit recognition of construction and supply chain risks

These changes do not directly reduce CAPEX or OPEX. Instead, they aim to reduce the probability of failure, thereby improving the overall investment profile of offshore wind projects.

An overview of Japan’s 2025 auction reforms and their strategic intent can be found in Offshore Wind Auction Reform in Japan (2025) .

4.4 The Centralized Method: Lowering Risk Rather Than Costs

Another major institutional shift is the introduction of the centralized method, under which government-led surveys and preparatory studies are conducted before projects are tendered.

The logic behind this approach is often misunderstood. The centralized method does not dramatically reduce construction costs. Instead, it targets risk reduction in the early stages of project development.

In theory, centralized surveys can:

- Reduce duplication of environmental and seabed investigations

- Lower uncertainty in project planning assumptions

- Improve financing conditions by stabilizing risk perception

The primary economic benefit therefore appears through lower risk premiums and more stable financing, rather than direct reductions in physical construction costs.

A detailed explanation of how the centralized method functions and its practical limitations is available in The Centralized Method for Offshore Wind in Japan .

4.5 Institutions Do Not Lower Costs — They Lower Failure Probability

A recurring misconception in offshore wind policy debates is that institutional reform should directly “make projects cheaper.” In reality, the more critical role of institutions is to reduce the likelihood of project failure.

Effective policy design can help avoid:

- Unexpected cost escalation late in the project lifecycle

- Financing breakdowns caused by unmanageable risk profiles

- Complete project withdrawal after significant sunk costs

These outcomes are not captured well by LCOE metrics, yet they are central to investor decision-making.

As Japan’s offshore wind framework continues to evolve, the success of reforms should be judged not by nominal price levels, but by whether projects reach construction and operation as planned.

With this institutional context established, the next chapter turns to project-level outcomes: how cost structures and IRR actually vary across Japan’s promotion zones, and what differentiates projects that are more likely to succeed.

Chapter 5: Cost Structure and IRR Distribution Across Japan’s Promotion Zones

Up to this point, we have examined offshore wind costs through the lenses of technology, LCOE limitations, and institutional design. However, these perspectives only become truly meaningful when applied to actual projects.

In Japan, offshore wind Promotion Zones are often discussed as if they were a homogeneous group of projects. In practice, they represent a diverse set of sites with fundamentally different cost structures and investment profiles.

This chapter analyzes how CAPEX, OPEX, LCOE, and IRR vary across Japan’s Promotion Zones, and why some projects are structurally more viable than others.

5.1 Why “Promotion Zone” Does Not Mean “High Profitability”

Designation as a Promotion Zone under the Renewable Energy Sea Area Utilization Act provides legal clarity and long-term occupancy rights. However, it does not guarantee economic viability.

From a project finance perspective, profitability is shaped by a combination of factors that are not standardized across zones:

- Distance to usable construction and O&M ports

- Water depth and seabed conditions

- Wave climate and seasonal offshore accessibility

- Grid connection capacity and curtailment risk

- Achievable turbine scale and layout efficiency

As a result, two Promotion Zones operating under the same auction framework can exhibit materially different IRR outcomes.

5.2 DeepWind’s Cost and IRR Modeling Approach

The project-level analysis referenced in this chapter is based on DeepWind’s proprietary cost model, benchmarked against publicly available data and the NEDO offshore wind cost framework.

For each Promotion Zone, representative assumptions are applied consistently, including:

- Representative water depth and distance from shore

- Assumed turbine capacity (13–18 MW class)

- Bottom-fixed or floating technology selection

- Distance to construction and O&M ports

- Standardized WACC and project lifetime assumptions

This approach does not attempt to predict absolute outcomes for individual bidders. Instead, it enables relative comparison across zones under a unified logic.

Full methodology and zone-by-zone results are detailed in: Japan Offshore Wind Promotion Zones: Cost & IRR Analysis .

5.3 IRR Distribution: What Differentiates Strong and Weak Projects

When Promotion Zones are viewed through an IRR lens, a clear distribution pattern emerges. Rather than focusing on precise numerical values, the structural drivers behind these differences are more informative.

- Zones with relatively higher IRR potential

Projects characterized by strong wind conditions, shallow water depths, shorter port distances, and the feasibility of bottom-fixed foundations. Among these factors, wind resource quality is especially critical, as it directly determines the upper bound of achievable revenue and cannot be improved post-selection. - Mid-range IRR zones

Projects that are technically feasible but constrained by port capacity, grid limitations, or seasonal installation windows. These zones often depend heavily on execution efficiency. - Structurally challenging zones

Sites requiring floating foundations, long installation distances, or exposed offshore conditions. In these cases, IRR is highly sensitive to cost escalation and schedule delays.

Importantly, these differences are largely driven by site characteristics rather than developer capability. Even best-in-class execution cannot fully overcome unfavorable physical constraints.

5.4 Practical Investment Criteria Beyond LCOE

For investors and developers, Promotion Zone evaluation requires a broader perspective than LCOE rankings alone. Key practical considerations include:

- Exposure to construction schedule slippage

- Operational access limitations driven by wave climate

- Grid curtailment risk affecting effective output

- Financing sensitivity to downside scenarios

Viewed this way, Promotion Zones should not be treated as a uniform asset class. They represent a portfolio of projects with distinct risk-return profiles.

This distinction explains why certain zones attract aggressive bidding, while others face hesitation despite similar headline capacity figures.

With these project-level dynamics in mind, the final chapter turns to strategic implications: how bottom-fixed and floating offshore wind should coexist in Japan, and what realistic development pathways look like for investors and policymakers.

Chapter 6: Role-Sharing Between Bottom-Fixed and Floating Offshore Wind in Japan

The preceding chapters demonstrate that offshore wind economics in Japan cannot be reduced to a single metric or technology choice. Instead, project viability emerges from the interaction of site conditions, cost structure, and institutional design.

Within this context, the question facing Japan is not whether bottom-fixed or floating offshore wind is superior, but how each technology should be deployed strategically.

6.1 Bottom-Fixed Offshore Wind: Japan’s Near-Term Anchor

Bottom-fixed offshore wind remains the most economically robust option where site conditions allow. Shallow water depths, shorter installation distances, and established construction methodologies enable comparatively stable CAPEX and predictable execution.

In Japan, bottom-fixed projects are most viable in:

- Water depths generally below 50–60 meters

- Coastal areas with access to suitable construction and O&M ports

- Regions with relatively moderate wave climates

Where these conditions align, bottom-fixed offshore wind offers the highest probability of achieving bankable IRR levels under current auction frameworks.

However, these sites are geographically limited. As development expands, remaining bottom-fixed opportunities tend to face increasing constraints related to ports, grid capacity, and competing maritime uses.

6.2 Floating Offshore Wind: A Necessity, Not an Optional Upgrade

For large portions of Japan’s coastline, floating offshore wind is not a premium alternative but the only feasible option. Steep bathymetry and rapid depth increases make bottom-fixed foundations impractical beyond a narrow nearshore band.

From a cost perspective, floating projects currently face:

- Higher and more variable CAPEX due to non-standardized platforms

- Additional OPEX driven by mooring systems and dynamic cables

- Greater sensitivity to schedule delays and weather windows

Yet the strategic value of floating offshore wind lies elsewhere. It unlocks wind resources that are otherwise inaccessible, expands the geographic scope of offshore wind deployment, and supports long-term energy security.

In this sense, floating offshore wind should be viewed as a structural requirement for Japan’s power system, rather than a technology that must first achieve parity with bottom-fixed costs.

6.3 A Phased Deployment Logic for Japan

A realistic pathway for Japan involves clear role differentiation:

- Bottom-fixed offshore wind

Deployed aggressively where site conditions permit, serving as the backbone for near-term capacity additions and early investment returns. - Floating offshore wind

Expanded gradually through demonstration, early commercial projects, and platform standardization, with cost reduction driven by learning effects rather than price-only competition.

This approach reduces systemic risk. Attempting to force floating projects into price structures designed for bottom-fixed installations has already proven unsustainable in earlier auction rounds.

Instead, aligning technology choice with physical reality allows capital to be allocated more efficiently and improves long-term market credibility.

6.4 Implications for Investors and Developers

For investors, the key implication is that offshore wind in Japan should be treated as a segmented market. Risk-return expectations must differ by technology and site type.

For developers, success increasingly depends on:

- Accurate assessment of execution risk, not just modeled LCOE

- Early alignment between technology choice and site constraints

- Financial structures resilient to cost volatility and schedule shifts

Projects that internalize these realities are more likely to survive beyond bid award and reach financial close.

Conclusion: Rethinking Offshore Wind Economics Through a Japanese Lens

Japan’s offshore wind challenge is often framed as a problem of high costs. In reality, it is a problem of misaligned assumptions.

Cost structures developed for mature European markets do not transfer cleanly to Japan’s physical, institutional, and infrastructural context. As a result, metrics such as LCOE, while useful for high-level comparison, are insufficient as standalone decision tools.

This Pillar article has shown that:

- Offshore wind costs in Japan are driven primarily by execution conditions

- IRR provides a more realistic lens for investment decision-making

- Promotion Zones represent heterogeneous risk profiles, not uniform assets

- Bottom-fixed and floating technologies serve fundamentally different roles

For Japan’s offshore wind market to mature sustainably, policy, finance, and technology choices must converge around these realities.

From DeepWind’s perspective, the path forward lies not in pushing prices lower at all costs, but in designing projects and institutions that acknowledge constraints, allocate risk transparently, and reward execution quality.

Only by doing so can offshore wind evolve from an aspirational policy target into a durable pillar of Japan’s energy system.

What is CAPEX?

CAPEX (Capital Expenditure) refers to the upfront investment required to build an offshore wind project. It includes turbines, foundations, transmission systems, and construction costs, usually incurred as a one-time large expense.

What is OPEX?

OPEX (Operational Expenditure) refers to the ongoing annual costs after a project begins operation. It covers maintenance, insurance, port fees, and other operating expenses that affect long-term project economics.

What is LCOE?

LCOE (Levelized Cost of Energy) is the average cost of electricity generated over the lifetime of a project. It includes both CAPEX and OPEX, and serves as a key benchmark to compare the competitiveness of renewable energy sources.

Japan’s offshore wind is no longer constrained by ambition — but by viability.📘 DeepWind Premium Report

A decision-oriented report synthesizing commercial viability, cost/revenue misalignment, supply-chain constraints, and Round 4 implications.

View the report (Gumroad)

- 🔍Market Insights – Understand the latest trends and key topics in Japan’s offshore wind market

- 🏛️Policy & Regulations – Explore Japan’s legal frameworks, auction systems, and designated promotion zones.

- 🌊Projects – Get an overview of offshore wind projects across Japan’s coastal regions.

- 🛠️Technology & Innovation – Discover the latest technologies and innovations shaping Japan’s offshore wind sector.

- 💡Cost Analysis – Dive into Japan-specific LCOE insights and offshore wind cost structures.