Japan’s Energy Strategy and the Frontline of the Global Market

As climate change mitigation and energy security are increasingly being questioned at the same time, making renewable energy a primary power source has become a shared global challenge. Among these, offshore wind power has been positioned as a “core technology for decarbonization,” given its relatively stable generation characteristics and its potential for large-scale deployment.

In Japan, however, the sea areas where conventional fixed-bottom offshore wind can be expanded at scale are limited. This is because fixed-bottom foundations—generally suitable for relatively shallow waters of around 50–60 meters—cannot sufficiently utilize the deepwater areas that surround the Japanese archipelago. Approximately 99% of Japan’s surrounding waters fall into depth conditions that are unfavorable for fixed-bottom offshore wind, meaning this constraint exists as a “geographic precondition” that comes even before policy design or technological choices.

Against this backdrop, what has regained attention in recent years is floating offshore wind. In this article, we examine floating offshore wind not merely as an advanced technology, but by organizing it through a structural lens that includes markets, costs, policy/regulation, and commercial viability, and we provide a systematic overview of the current situation and future outlook in Japan and globally.

Why Floating Offshore Wind — and Why Now?

The reason floating offshore wind is often described as the “next game changer” lies not only in technological progress, but also in macro drivers such as rising geopolitical risk and the reconfiguration of energy supply structures. In particular, for Japan—where dependence on fossil fuels remains high—the importance of offshore wind as a means to increase the share of domestically available energy has been growing year by year.

A more detailed explanation of this context, including global market trends, is covered in the following article.

👉 Why Floating Offshore Wind Now? | Background and Market Context

Structural Drivers Making Floating Offshore Wind Unavoidable

Deepwater as an Untapped Energy Resource

The waters around Japan are characterized by steep seabed topography, with large areas exceeding 100 meters in depth. While Japan’s theoretical offshore wind potential is often cited as exceeding 100 GW, only a portion of that resource is accessible with fixed-bottom technology. Floating offshore wind is the only practical means of unlocking deepwater resources that could not previously be utilized as a source of energy supply.

Social Acceptance and EEZ Expansion

Floating offshore wind can be installed farther offshore, which can relatively mitigate social acceptance challenges such as visual impact, noise, and competition with fisheries. In addition, amendments to Japan’s legal framework governing the use of sea areas for renewable energy have made it institutionally possible to deploy projects in the EEZ (Exclusive Economic Zone), greatly easing spatial constraints.

That said, opening access to the EEZ does not imply “automatic commercialization.” Constraints related to costs, construction execution, and financing—discussed later in this article—still remain decisive.

Linkage with Global Markets

Floating offshore wind is not a challenge unique to Japan. Similar adjustments are ongoing in Europe, the United States, and across Asia—each grappling with the gap between “technical feasibility” and “commercial bankability.” Understanding the global deployment phase is essential for putting Japan’s market into perspective.

👉 A Detailed Analysis of Floating Offshore Wind Market Trends in Japan and Globally

An Overview of Floating Platform Technologies

The core of floating offshore wind lies in floating platform design that enables stable power generation under harsh metocean conditions. In engineering terms, the critical requirement is to balance “static stability”—driven by the relationship between the center of gravity and the center of buoyancy—with “dynamic stability,” which suppresses motion induced by waves and wind.

The four platform types most commonly considered today are as follows.

- Semi-submersible: Suitable for mid-depth waters; relatively high constructability and flexibility

- Spar: Suitable for deep water; highly stable, but strongly constrained by port and draft requirements

- Barge: Structurally simple, but requires robust motion-mitigation measures

- TLP (Tension Leg Platform): High efficiency, but with a high level of installation complexity

Importantly, the “fit” of each platform type is not determined by technical characteristics alone. Port conditions, construction/installation capabilities, and risk allocation can fundamentally change which designs are commercially suitable.

👉 Floating Offshore Wind Platform Design: Fundamentals and Key Types

The Cost Structure and LCOE Reality of Floating Offshore Wind

The largest barrier to commercialization of floating offshore wind is not simply “high cost,” but rather the fact that its cost structure is fundamentally different from that of fixed-bottom offshore wind. While floating projects do have room for reductions across individual CAPEX and OPEX components, structurally “sticky” cost elements still push up overall LCOE.

CAPEX: Where Costs Can Fall — and Where They Do Not

CAPEX for floating offshore wind can be broadly decomposed into (1) the turbine, (2) the floating structure, (3) mooring and anchors, (4) construction and installation, and (5) grid connection infrastructure. Among these, the turbine has many common elements with fixed-bottom projects, and is a category where cost reductions are relatively expected through turbine upscaling and learning/scale effects.

By contrast, floating structures and mooring systems are highly site-dependent, which limits the effectiveness of standardization and mass production. Designs must be adapted to conditions such as water depth, wave climate, currents, and seabed properties. As a result, these components can easily drift toward a “one-off” production structure—becoming a key bottleneck for CAPEX reduction.

In addition, during the construction and installation phase, towing and placement schedules are strongly dependent on weather conditions. This does not only affect direct installation costs; it also raises CAPEX through contingency allowances and EPC risk premiums that reflect schedule-delay risk. Although such indirect costs are difficult to see in surface-level comparisons, their impact on LCOE is not negligible.

OPEX: The Gap Between Digital Expectations and Reality

For floating offshore wind, OPEX reductions are often expected through advanced O&M practices such as unmanned inspections using drones and ROVs, and condition monitoring via digital twins. However, these technologies are not a “magic solution” that dramatically lowers OPEX.

Under the harsh metocean conditions around Japan, access limitations themselves become a binding constraint for O&M. As a result, while it may be possible to reduce inspection frequency or improve work efficiency, in practice it is difficult to cut safety margins or redundancy. OPEX therefore tends to “bottom out,” and the scope for OPEX reductions large enough to offset CAPEX disadvantages is limited.

Why LCOE Declines Are Structurally Slow

The primary reason floating offshore wind LCOE does not fall as quickly as fixed-bottom is that scale benefits do not fully translate. In fixed-bottom offshore wind, standardization of foundation concepts and installation approaches has advanced, allowing unit costs to decline as project sizes grew.

In floating projects, by contrast, site-specific differences are large, and design, construction, and risk assessment are effectively “re-done” for each project. As a result, even when project scale increases, CAPEX, OPEX, and financing costs do not decline proportionally, making LCOE improvement non-linear and gradual.

Moreover, in Japan, natural hazards such as typhoons and earthquakes are often reflected as additional financing and insurance costs, which tends to tighten WACC assumptions. This cannot be resolved by technology improvements alone, and it remains as a structural factor that pushes LCOE upward.

The Key Perspective for Cost Discussions

When discussing floating offshore wind costs, the critical point is to separate (a) an expectations-driven narrative of “costs will fall in the future,” from (b) a reality-driven analysis of “which components do not fall easily.” While there is certainly room for improvement through turbine upscaling and design optimization, these factors alone do not automatically restore commercial viability.

Understanding this structure correctly helps avoid excessive optimism or undue pessimism, and leads to more realistic commercial decision-making.

For a deeper breakdown of the numbers and LCOE analysis, see the following article.

👉 The Real Cost Structure and LCOE of Floating Offshore Wind

Why Floating Offshore Wind Can Be Technically Feasible Yet Still Not Commercial

In Japan, the technical feasibility of floating offshore wind has already been increasingly confirmed at the demonstration stage. Multiple projects have delivered meaningful outcomes in areas such as platform stability, power generation performance, and the fundamentals of mooring system design.

Nevertheless, floating offshore wind has remained limited in commercialization. Behind this lies a structural gap between “technical feasibility” and “commercial feasibility”.

This gap cannot be explained by a single factor such as high cost or immaturity of technology. The issue is that floating offshore wind faces constraints that become visible only when scaling up.

First is the difference between demonstration scale and commercial scale. In demonstration projects of several MW to several tens of MW, uncertainty in design, construction, and operations is relatively contained, and there is often more room for adjustment through stakeholder discretion. In gigawatt-scale commercial projects, however, critical elements—port capability, installation vessel availability, procurement, and schedule management—become “systematized,” and can no longer be managed through project-by-project optimization alone.

Port infrastructure, in particular, tends to become a bottleneck for floating offshore wind. Assembling, staging, storing, and towing large floating structures require expansive yards, deep-draft quays, and heavy-lift crane capacity. Such facilities cannot be developed quickly. If port development does not keep pace, projects may stall at the execution stage even when they appear feasible on paper.

Second is construction execution and risk allocation. Floating offshore wind is sometimes described as “not requiring jack-up installation vessels,” but in practice this does not mean construction risk disappears across the full value chain. Weather dependency is high in mooring, towing, and installation phases, and schedule delays translate directly into financing costs and insurance premiums. These uncertainties tend to crystallize not in the developer’s narrative, but in the assessment frameworks of lenders and insurers, which in turn tightens financing terms.

In addition, Japan’s natural hazard profile influences commercial viability. Typhoons, earthquakes, and tsunamis may be addressed in engineering design, but they are still added on top of project evaluation as “probabilistic risks.” This is not something technology can fully eliminate, and it remains a structural factor pushing LCOE upward through risk premiums.

As these factors overlap, floating offshore wind is often perceived as “technically feasible, but commercially immature as a delivery system that includes finance, construction, and infrastructure.” The key point is that this is not merely an individual developer’s problem; it is a structural challenge faced by the market as a whole.

When we take a broader view of Japan’s demonstration projects, we can see these common constraints repeatedly emerging.

For a detailed case-based discussion, see the following article.

👉 Floating Offshore Wind Demonstrations: Case Studies and Structural Challenges

Commercializing floating offshore wind requires not only technology innovation, but also simultaneous evolution of the overall delivery environment, including ports, construction capacity, and finance. In the next chapter, we will look at domestic and international project examples to examine how these structural challenges manifest in practice.

Common Patterns Emerging from Domestic and International Project Examples

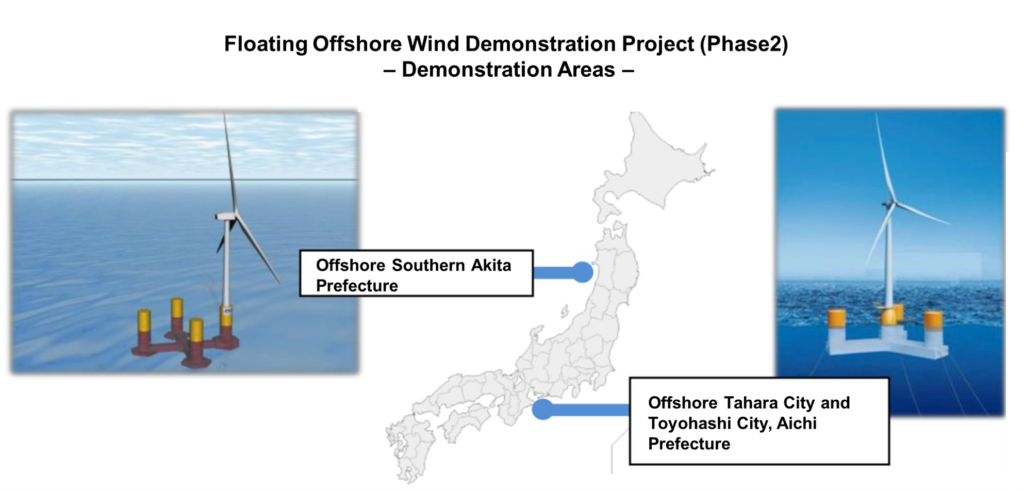

In Japan, floating offshore wind demonstrations have progressed in areas such as Goto and off Akita. These projects have delivered important outcomes as technology validation efforts, while also clarifying the challenges that appear when scaling up.

Meanwhile, international markets have produced earlier examples under institutional and market conditions different from Japan’s. Among these, a notable angle is the overseas deployment of Japanese technologies.

👉 Japanese Floating Technology Goes Global: Brazil’s “Aura Sul” Project Explained

Policy, Certification, and Japan-Specific Risks

Floating offshore wind requires layered compliance across legal frameworks governing sea-area use for renewables, IEC standards, and third-party certification. In addition, Japan-specific risks—typhoons, earthquakes, and tsunamis—affect design assumptions as well as financing and insurance conditions.

👉 Floating Offshore Wind in Japan: Policy, Certification, and Key Challenges

The Post-2030 Technology & Market Roadmap (A Practical View)

Floating offshore wind beyond 2030 will not move along a simple straight line from “demonstration to commercialization.” The key question is how well the timing of technology progress can synchronize with practical enabling conditions such as ports, construction capacity, and finance. This chapter outlines a roadmap from an execution-oriented perspective.

Technology Progress Will Only Deliver “Stepwise” Effects

Toward 2030, progress is expected across technology areas such as 20+ MW turbines, lighter floating structures, and improved durability of dynamic cables. However, such advances are not a silver bullet that instantly drives down LCOE.

Upscaling reduces the number of units, but it also increases the difficulty of platform, mooring, and installation design, while tightening port requirements and construction constraints. For these reasons, the effects of technology progress are likely to materialize in a partial and stepwise manner.

Ports and Construction Capacity Define the Upper Bound of Scale

The most decisive constraint for post-2030 deployment remains ports and construction capability. Floating projects require port functions that assume assembly, staging, and towing of large structures—and without these, project scale is physically capped.

Because port development requires multi-year investment decisions, the market faces a structural problem: when demand visibility is unclear, the supply side cannot easily justify upfront investment. This is why the market may continue to see a phase where “technology is ready, but deployable scale remains limited.”

A “Stepwise Localization” Supply Chain Is the Realistic Path

Building a fully domestic supply chain for floating structures and mooring components is unlikely in the short term. A more realistic scenario is a hybrid model combining overseas procurement with domestic manufacturing.

By localizing specific components and processes while sharing the remainder with overseas suppliers, the industry can accumulate execution experience and gradually increase localization. Whether this works depends heavily on pipeline continuity and the predictability of orders.

Financing Conditions Improve Only on an “Evidence-Based” Track Record

Financing conditions will not automatically improve after 2030. What lenders and insurers care about is reducing uncertainty based on operational evidence.

Not a single successful pilot, but multiple projects completed and operated under comparable conditions—this is what begins to reduce risk premiums. Therefore, the key to the roadmap is not a one-off flagship project, but the accumulation of repeatable, mid-scale projects.

A Realistic Post-2030 Trajectory

Based on the above, floating offshore wind beyond 2030 is likely to progress through:

- Stepwise commercialization in selected regions and projects

- Cautious expansion that assumes a “timing mismatch” between technology and enabling conditions

- Growth conditional on synchronized development of ports, construction capability, and finance

—in other words, this is the most realistic path.

Rather than a market that accelerates sharply after 2030, it is more consistent with execution reality to view floating offshore wind as a market that expands quietly where conditions are met. Whether stakeholders can align on this premise will strongly influence success in the next phase.

👉 Floating Offshore Wind: Post-2030 Technology and Market Trends

👉 Floating Offshore Wind in Japan: EEZ Expansion and Extreme-Environment Deployment

Who Is Best Positioned for Floating Offshore Wind? (By Player Type)

Floating offshore wind is not equally promising for every type of player.

While technical potential is often emphasized, commercial feasibility in practice is heavily shaped by differences in capital strength, risk tolerance, and execution capability. In this chapter, we organize “cases that fit” and “cases that are structurally difficult” by player type.

Major Utilities and Integrated Energy Companies

Major utilities and integrated energy companies are relatively well positioned for floating offshore wind. They can take a long-term view as an electricity supply asset, and prioritize portfolio-level optimization over short-term profitability.

In particular, their expertise in grid operation and long-term O&M becomes a strength in phases where floating projects carry high uncertainty. On the other hand, investment decisions can be cautious, and without clear institutional support and bankable revenue visibility, they may tend to limit project scale.

▶ Favorable conditions: long-term horizon / balance-sheet capacity / grid & operations expertise

▶ Constraints: alignment with short-term IRR requirements; policy uncertainty

General Contractors, Shipbuilders, and Marine Engineering Players

General contractors, shipbuilders, and marine engineering firms can play central roles in the implementation phase of floating offshore wind. Their existing capabilities often align with manufacturing floating structures, mooring design, and offshore construction.

However, caution is required if these players move to the front as the project owner/developer. If they take on market risk and power price exposure on top of construction/manufacturing risk, risk concentration can become excessive.

▶ Favorable conditions: EPC/supplier role / risk-sharing structure

▶ Risk: balance-sheet pressure from developer-style risk stacking

Trading Houses and Investment Players (Finance / Infrastructure Funds)

Trading houses and infrastructure investors need a selective approach to floating offshore wind. Project risks are high and vary significantly by site, making portfolio diversification less effective than in more standardized infrastructure assets.

As a result, rather than broad early-stage participation, a more realistic approach is targeted investment in projects where policy conditions are clearer and execution structures are already established. Overexposure to early demonstration phases can distort the risk–return balance.

▶ Favorable conditions: entry at later stages / risk-limited investment structures

▶ Caution: excessive expectations for early demonstration phases

International Developers and Technology Holders

International developers and technology holders can play important roles in Japan’s market, but their existing business models cannot be applied as-is. Without adaptation to Japan’s natural conditions, port constraints, and policy design, technology advantages may not fully translate into project outcomes.

The key to success is collaboration with domestic partners, with clearly defined roles and risk allocation. Solo entry can lead to higher-than-expected costs and coordination burdens.

▶ Favorable conditions: collaboration with domestic partners

▶ Common failure mode: direct transplantation of overseas models

Cases That Are Not Well Suited: Short Payback / Optimism-Driven Entry

The least suitable approach to floating offshore wind is entry premised on short payback periods or rapid cost declines. Floating projects are structurally uncertain and tend to follow a slower learning curve, making it unrealistic to expect the same speed of cost reduction as fixed-bottom offshore wind.

Entry justified mainly by demonstration results or optimistic assumptions about future technology can face a significant gap once the project moves into commercialization.

Summary of This Chapter

Floating offshore wind is not a “growth market anyone can enter.” It is a field that becomes viable only under specific conditions.

Players best positioned are those with a long-term horizon, high risk tolerance, and strong execution capability—while also being able to define and limit their role appropriately.

Understanding this reality correctly is a prerequisite for positioning floating offshore wind not as a “dream technology,” but as a sustainable commercial domain.

Conclusion | Floating Offshore Wind as a “Conditional Commercial Reality”

Floating offshore wind is a technology with significant theoretical potential for Japan. It is one of the few options capable of simultaneously improving energy self-sufficiency and accelerating decarbonization by overcoming deepwater geographic constraints.

At the same time, as discussed throughout this article, floating offshore wind is also a field where technical feasibility alone does not translate into commercial viability. Unless factors such as cost structure, port and construction capability, financing conditions, and policy design evolve together, commercialization will remain limited.

In other words, floating offshore wind should be positioned not as a “dream technology that will inevitably bloom someday,” but as a conditional commercial reality that expands only when enabling conditions align.

What matters is seeing reality accurately—neither with excessive optimism nor undue pessimism. Overconfidence leads to poor commercial decisions, while underestimation narrows future options. The debate around floating offshore wind requires a calm perspective that spans technology, markets, policy, and finance.

Ultimately, whether Japan can deploy floating offshore wind sustainably will depend not on the success of individual flagship projects, but on the ability to establish repeatable delivery models. The capability to evaluate that success will be the shared challenge for developers, investors, and policymakers alike.

DeepWind will continue to analyze floating offshore wind not through “expectations,” but through “structure,” and provide insights grounded in commercial reality.

📘 DeepWind Premium Report

Japan’s offshore wind is no longer constrained by ambition — but by viability.

A decision-oriented report synthesizing commercial viability, cost/revenue misalignment, supply-chain constraints, and Round 4 implications.

- Commercial viability (CAPEX/OPEX vs revenue)

- Supply-chain & execution constraints

- Round 4 / re-auction implications